Uncovering the Truth Behind the Women’s Suffrage Movement

What the history books never taught you.

by PEYTON SURPRENANT ★ MARCH 30, 2021

March is Women’s History Month! So... what does that mean?

It’s OUR TIME to celebrate not only the amazing women in our lives, but the women who paved the way for the feminist movement. When people think about women’s rights in the United States, it goes back to 1848 at the Seneca Falls Convention—the nation’s first official women’s rights convention. Led by prominent figures like Elizabeth Cady Stanton, Lucretia Mott, and Susan B. Anthony, this convention has regarded these notable white suffragettes as the founding mothers of the women’s rights movement. But where did this movement actually begin? This women’s history month, let’s take time to acknowledge how Indigenous and Black women are responsible for the original ideas of feminism.

When early suffragettes were looking for inspiration on what a society with gender equality would look like, they turned to Haudenosaunee women. Elizabeth Cady Stanton and Lucretia Mott visited the Haudenosaunee community (right here in Central New York!) and never fathomed a seeing an egalitarian world where women, in most cases, had positions of power. Ultimately, these white suffragettes took Indigenous ideologies as their own and proceeded to exclude Indigenous women from their movement.

Even before Seneca Falls, Black women were gathering in Philadelphia and debating women’s rights. Black activists Jarena Lee and Maria Stewart were writing Black feminist texts and giving speeches in the 19th century. Black women were already having their own conversations about Black women’s liberty. Women of color were displaced from the women’s rights movement because white women saw their race first and foremost. Women of color had to create their own feminist movement because they were grappling with the intersection of their race and gender.

The 19th amendment was finally passed in 1920, but it came with many omissions—women of color weren’t fully granted the right to vote. Full universal suffrage didn’t happen until 1965. While we remember Rosa Parks for her infamous bus boycott, the rest of her work involved advocating for voter’s rights. Black women like Augusta T. Chissell and Margaret Gregory Hawkins, worked hard to make voting fairer and more equitable for all individuals. This led to the Voting Rights Act of 1965 being passed, made possible by the Black women who championed for their rights.

So what can we make of all of this? Truth be told, there is so much more to the history of Indigenous and Black women’s rights activists, but their stories are rarely heard. What’s important to understand is that not only did women’s rights begin with women of colors’ work, but women of color were largely excluded from the mainstream women’s rights movement. Meanwhile, white women were the faces of the suffrage movement and the ones who reaped the benefits.

Let’s be clear—women’s history is not complete without all women’s history. 21st century feminism is doing better at being all inclusive and recognizing intersectionality, but it isn’t doing enough. We need to begin by reevaluating our history and giving credit where it's LONG overdue. To end this women’s history month, I encourage you to think about the women of color who built the backbone of our modern day feminist movement. Here are some incredibly radical and revolutionary Black and Indigenous women to reflect upon this month and all months:

Harriet Forten-Purvis (1810-1875)

During Purvis’ time, women were excluded from Black led abolitionist movements, so she founded the Philadelphia Female Anti-Slavery Society. Her organization boycotted products made through slave labor, which gave Black women a voice through purchasing power. She spent her life lobbying for women’s suffrage and spoke at the National Women’s Rights Convention.

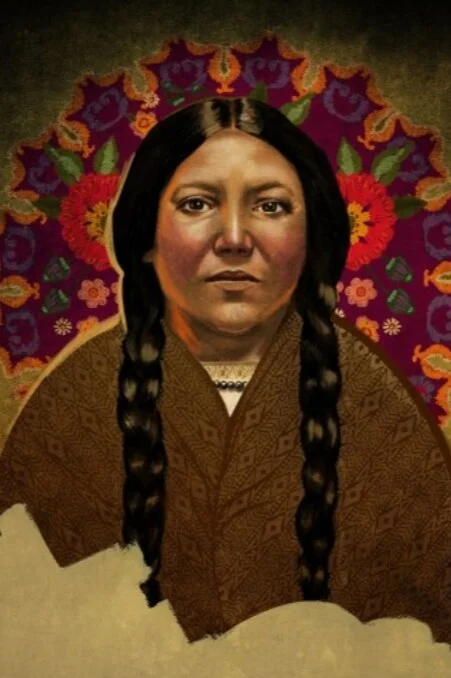

Zitkála-Šá (1876-1938)

Zitkála-Šá was a Yankton Sioux of South Dakota who joined the pan-Indian movement in lobbying for the Indian Citizenship Act of 1924. She helped in making Native Americans be recognized as citizens under the law through the National Council of American Indians, which she founded in 1926.

Sojourner Truth (1797-1883)

Truth was an avid suffragette as well as an escaped slave known for her infamous “Ain’t I a Woman” speech at the Women’s Rights Convention of 1851. She dedicated her life to championing for abolition and women’s rights. A statue of her lies within the United States Capitol.

Marie Louise Bottineau Baldwin (1863-1952)

Baldwin was raised to be a political advocate, as her family spent their life representing the rights of the Ojibwa/Chippewa Nation. She was appointed as a clerk in the Office of Indian Affairs in 1904 by the president and used her platform to demand that Native women must not assimilate to participate in society. She was the first woman of color to graduate from the Washington College of Law.

Wilhelmina Kekelaokalaninui Wideman Dowsett (1861- 1929)

A Native Hawaiian, Dowsett began to advocate for women’s rights after the annexation of Hawai’i. She created the Women’s Equal Suffrage Association of Hawai’i, a grassroots organization that gave women in Hawai’i the right to vote in 1920. She also petitioned for other Native women to gain voting rights.

Ida B. Wells 1862-1931

Wells was a radical journalist that worked to expose the harsh reality of racism in the United States. She was the co-owner of the Memphis Free Speech and Headlight newspaper where she discussed the lynching crisis of Black Americans. She organized her own suffrage club, Alpha Suffrage Club, and critiqued white suffragettes for excluding women of color from their cause.

As Women’s History Month comes to a close, let’s continue celebrating all the beautiful and strong women who constantly inspire us! There is never a wrong time to applaud the women before us for all they have done. To make them proud, keep educating yourself and questioning what your history books have taught you. Remember, your voice matters!

Cover photo credit: The New York Times (Steffi Walthall)